During the intense winds and flooding of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, electrician Joseph McAllister was driving around South Beach, Staten Island, New York trying to help his neighbors stranded in the dark. After returning from his house to get a flashlight, McAllister was shocked at what he saw. The wind had pushed the roof off a large catering hall behind his house and came crashing down, almost landing on a kid.

McAllister doesn’t want to witness this again. That’s why he is using his role as President of the South Beach Civic Association, along with his wife and VP, RoseAnn McAllister, to ensure their community is better prepared for the future coastal storm—events that are becoming stronger and more frequent.

The McAllisters are pleased that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New York District has a coastal storm risk management plan in place that will help reduce coastal impacts along Staten Island’s east coast. This includes their community of South Beach, as well as Midland Beach, New Dorp Beach, and Oakwood Beach during future coastal storms.

Staten Island is the southernmost borough of New York City and is situated at the southernmost point of the state of New York. The borough is separated from the adjacent state of New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and Kill Van Kull waterways and from the rest of New York State by New York Bay.

New York City was severely impacted by Hurricane Sandy. Staten Island was hardest hit, experiencing winds up to 80 mph, and a 20-foot storm surge that washed away homes along the borough’s East coast. This didn’t stop the McAllister’s and the rest of their South Beach Community Emergency Response Team from trying to help their community.

RoseAnn McAllister says it was like the end of the world. “As we drove around, we saw cars flipped over, laying in deep water that smelled like spilled diesel fuel. People screaming from their roofs for help and some walking around in a trance because they were in shock that their homes were gone, family pets gone, everything destroyed. It was terrible to see. At a high vantage point we were able to see that our house and whole block was surrounded by this deep, deep water. We were minutes away from being drowned.”

Hurricane Sandy resulted in 24 deaths on Staten Island, more than any other borough. Most of them occur on the East and South shores. Many of the victims drowned in their homes.

This wasn’t the first time the borough of 468,374 residents was severely impacted by a hurricane. Other recent major storms included the Nor’easter of December 1992, the March storm of 1993, Hurricane Irene in 2011.

Then came Sandy the following year, which impacted critical infrastructures, including nearly 7,300 residential and commercial properties, the Staten Island Railway, fire and law enforcement stations, Staten Island University Hospital, and schools which served as shelters in the aftermath of Sandy.

Getting ready

Getting ready

To better prepare Staten Island for another Hurricane Sandy, the Army Corps is working on a long-term solution. Frank Verga, Project Manager, New York District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers says the size and design of this project is for a storm bigger than Sandy. “If this project was already in place, it could have alleviated Sandy’s damages.”

Verga, who is also a Staten Island resident, says the project will include a nearly 5-mile seawall that will provide a line of protection, a barrier to the water that will come in from an ocean event, and on the interior. It also will have all-natural ponding areas that will allow water to hold until events are finished.

The complex project has been years in the making because it covers such a large area and requires major design and coordination with multiple agencies including the State of New York, City of New York, National Park Service, and local community groups like the South Beach Civic Association.

The Association has held many public meetings with the Army Corps to discuss the project. “The purpose of our organization is to deal with quality-of-life issues for our residents,” says Joseph McAllister, who has lived on Staten Island for 60 years and has overseen the South Beach Civic Association with his wife since 2000.

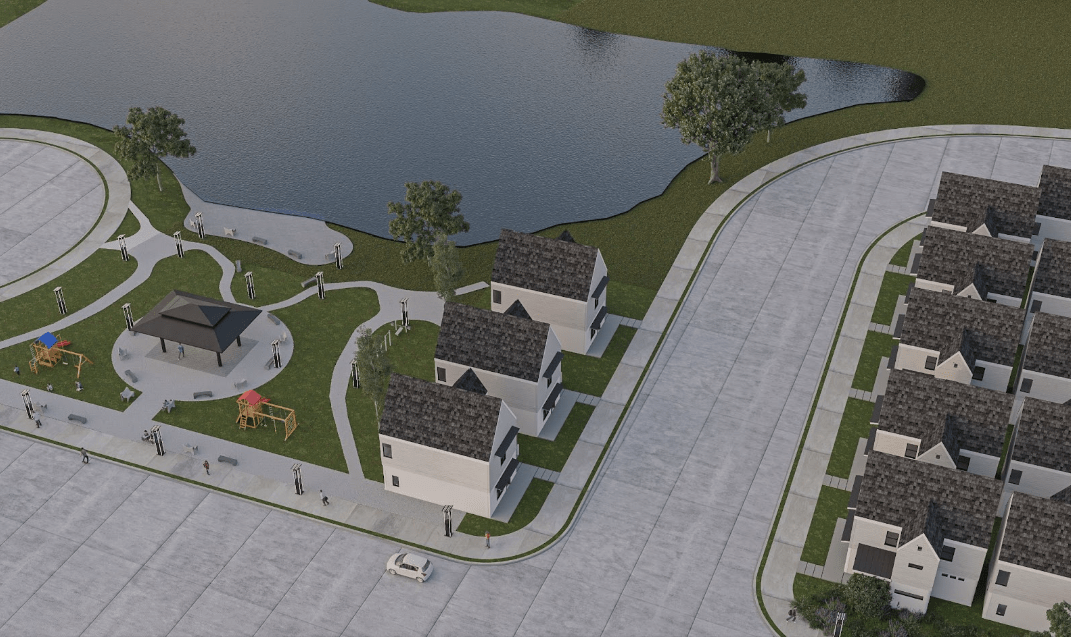

Now that the project is starting to move forward, the Army Corps will be attending more meetings with the McAllister’s to discuss the project details that will include the following. First, all-natural ponding areas will be constructed on land that will receive and store stormwater runoff from large drainage areas to allow water to hold until storm events are finished. The ponds will be in South Beach, where construction is taking place now, and later in Midland Beach and in Oakwood Beach.

In addition, an earthen levee, road closure gate and tide gate will be constructed near Great Kills Park to keep tidal waters back. Tide gates will also be constructed in Oakwood Beach along the existing creek, as well as construction of a flood wall around the Oakwood Beach WasteWater Treatment Plant that will also keep water back.

Following this, the approximate 5-mile-long seawall, with an elevation of 21 feet will be constructed. The wall will run along the east coast of the borough, from the edge of Fort Wadsworth in the north, that’s just south of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, to Oakwood Beach in the south.

In front of the seawall in the Oakwood Beach area, a tidal wetlands will be created. The wetland’s vegetation will help stabilize the land, reduce waves and coastal erosion, and will help build the ecological resilience of the coast to respond to increasing sea -level rise.

In front of the seawall in the Oakwood Beach area, a tidal wetlands will be created. The wetland’s vegetation will help stabilize the land, reduce waves and coastal erosion, and will help build the ecological resilience of the coast to respond to increasing sea -level rise.

As part of the seawall structure, the Army Corps will be reconstructing the existing boardwalk that will continue to provide public access to Midland Beach and South Beach. As the Army Corps performs this work, New York City has plans to build six natural and recreational areas in and around the seawall that will include bike paths, public spaces, and beach access. The McAllister’s are looking forward to this work being done.

“We absolutely support the sea wall solution,” Joseph says. “We understand that the Army Corps wants to do it right and that it takes time and planning. I understand this. My father was a civil engineer with the government going way back.”

RoseAnn says association members are frustrated. “They want the seawall now. I completely understand this, but I tell them, ‘Listen, it’s better to do it right. Do the planning right, so we don’t have to do it again. You do it right the first time.’”

The entire project is expected to be completed within a decade. After this the Army Corps will monitor it for any necessary changes due to future sea level rise, while the State and City of New York will be responsible for operating and maintaining the project.

“In the future our hope is to get that seawall so we can protect many generations down the road besides ourselves,” RoseAnn says. “Our kids, our grandchildren, and their families. So, they don’t have to worry about getting a seawall. So, their community has quality of life and are not fearful that something like another Sandy could happen again and wash away their homes and businesses.”

Dr. JoAnne Castagna is a public affairs specialist and writer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New York District. She can be reached at JoAnne.Castagna@usace.army.mil