The “Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS),” a Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) product that supplies data regarding labor market churn, indicates an ongoing tightening of the nation’s construction labor market. This is surprising for several reasons.

First, between January 2020 and January 2021, industry employment fell by more than 200,000 jobs. Second, after expanding rapidly during the third quarter of 2020, the broader economy stalled in the fourth quarter of 2020 and the beginning of 2021. Finally, a number of industry-specific leading indicators, including Associated Builders and Contractor’s Construction Backlog Indicator, and the Architecture Billings Index, suggest lingering softness in demand for construction services.

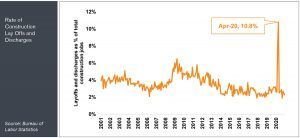

Nonetheless, JOLTS data indicate that construction firms are clinging to their workers more aggressively, with layoff activity declining during late last year. This represents a departure from labor market dynamics registered in the first few months of 2020.

In March 2020, as the pandemic imposed its will on American society, contractors slimmed down their workforces as project work slowed or came to a standstill. More than 600,000 construction workers were laid off or discharged during that month alone, more than 50% above the level registered during the previous worst month on record (April 2009). April 2020 was even worse, with 709,000 workers, or 10.8% of the total construction workforce, laid off or discharged.

When the pandemic began, some thought (and hoped) that the massive job losses observed in March and April would mitigate the skilled labor shortages that have frustrated construction firms for years. That simply has not happened to any meaningful degree.

Despite the availability of stepped-up unemployment insurance benefits from the federal government at that time, many construction workers clung to their jobs. The number of construction workers who quit reached a six-year low in April 2020, but has since rebounded to roughly normal levels.

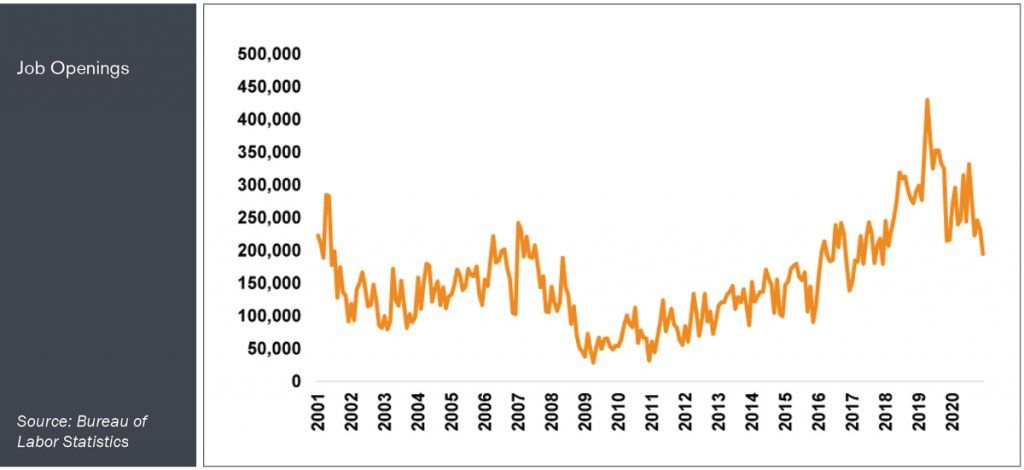

Indeed, JOLTS’ data indicate that the construction labor market has returned toward normalcy with astonishing rapidity. For example, both total hires and job openings were down only slightly on a year-ago basis by 2020’s conclusion.

Presently, the number of job openings is equal to 2.6% of construction employment (195,000 unfilled positions). While that is the lowest proportion registered since December 2017, it is higher than the average proportion of job openings observed from 2014-2017. It also is higher than any month during the 2008-2013 period, indicating that job openings are low by recent standards but not especially low in the context of the past decade.

When the pandemic began, some thought (and hoped) that the massive job losses observed in March and April would mitigate the skilled labor shortages that have frustrated construction firms for years. That simply has not happened to any meaningful degree.

The return toward normalcy also is apparent in the quits rate, which shows that contractors are struggling to find and retain skilled labor. In December 2020, there were 13,000 more workers who quit their construction jobs than were laid off or discharged by their employers. This was just the 17th month in the past 20 years during which quits exceeded layoffs and discharges—a clear indication of labor market tightness.

There is more. In the midst of a gut-wrenching, economy-destroying pandemic, average hourly earnings of construction employees reached their highest level on record in January 2021 ($32.11), and average weekly hours worked rose to their highest level since 2019’s third quarter.

This is what one might expect from a strong economy operating under normal circumstances, not one facing a lingering pandemic and elevated unemployment. At the time of this writing, the construction unemployment rate is a still lofty 9.4%.

How can it be that contractors are clinging to workers and still cannot fill many available positions during the midst of a pandemic? One possible explanation revolves around regional disparities. Parts of the US like the Southeast, Texas, Colorado and segments of the Mid-Atlantic region have surging residential marketplaces and reasonably stable levels of nonresidential activity.

Other areas, like the Northeast and certain parts of the Midwest, where much of the industry’s job losses have occurred and where population has been stagnant or declining for years, are home to an abundance of unemployed construction workers. In other words, the job openings are concentrated in certain regions while idle labor is concentrated in others.

3 Things to Watch

- Will workers come back?

According to the Census Bureau, more than 60% of construction workers who lost their jobs during the Great Recession left the industry by 2013. Many of these workers found positions in other industries, while others retired altogether. - Will the nonresidential segment catch up?

The residential construction market has surged to unprecedented heights, with residential spending surpassing $700 billion in December 2020 (seasonally adjusted, annual rate), the highest level ever recorded and 20% higher than in December 2019. Nonresidential spending, on the other hand, is down almost 5% year-over-year, with the hot single-family construction market driving both labor and materials costs higher. - What about public construction?

Thus far, public construction has held up well thanks in large measure to pre-existing backlog and construction’s enviable status as an essential industry. But with state and local government finances compromised by the crisis, it is conceivable that public work will dry up absent a federal stimulus package, resulting in more worker availability but fewer contracts.

Anirban Basu is the Chief Construction Economist for Marcum LLP, a leading national accounting and advisory services firm dedicated to helping entrepreneurial, middle-market companies and high net worth individuals achieve their goals.